Original article by Michiel Bussink, published on Bodhi, with the headline: “Tibetan Monk with Frisian Roots.”

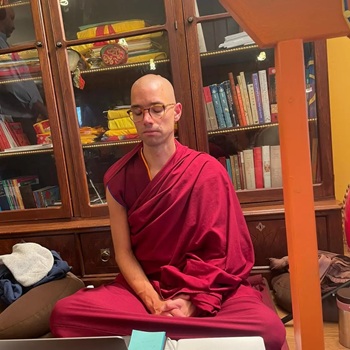

From an athletic youth in the Frisian countryside, by way of Jewish Studies in Jerusalem, and to the initiation as a Tibetan Buddhist monk high in the Himalayas: that is the path of Karma Ösung. He is now in the Netherlands to supervise a course on interconnectedness in the world. “Society is never separate from what you do.”

Can the thousand-year-old precepts from the time of the Buddha mean anything for our current society with its conflicts and polarized relationships? We asked Karma Ösung (b.1986), a Tibetan monk with Frisian roots. In these past weeks, Ösung has returned to the Netherlands to supervise the course ‘Mutual Connectedness’ organized by the Tibetan Buddhist sangha, Nalandabodhi. It is about our ever-shrinking world, in which it is crucial to see our mutual connectedness to each other, to the earth, and how to actively work with a global community.

Monastic Rules as an Inspiration for Society

The six-part name on his Facebook page immediately gives an impression of the life path of Fransiscus Ismaël Karma Ösung Melchers-Kusters. The two first names disclose his Catholic upbringing, the following two surnames honor both his father and his mother. And he has been known as ‘Karma Ösung’ since receiving his monk ordination in the Tibetan Buddhist Kagyü tradition in 2022.

His ordination took place in the Rumtek monastery in the Indian state of Sikkim, at an altitude of 1500 meters in the Himalayas. And included taking a set of vows, based on the Vinaya, the rules that the Buddha himself drew up for monks and laymen.

In addition to serving as a guideline for the individual lives of monks and laymen, the Vinaya also includes socio-political instructions. “Decision-making within a community based on the Vinaya is always based on consensus and commonality,” says Ösung. “So as long as even one individual disagrees with something, you continue talking. It doesn’t matter whether you are Buddhist or not. It’s about the fundamental equality of everyone. That was very radical in the time of the Buddha, when the caste system was very rigid.”

According to Ösung, this consensus rule can also be used in our current society, to involve as many perspectives as possible in decision-making. He mentions Costa Rica as an example, which not only wants to ensure equal access to education and care for all population groups, but also gives nature a ‘voice’ in decisions.

Beyond the Differences

But how do you deal with people who are not looking for cooperation and who seem to be focused primarily on power and self-interest? “Try to see beyond the differences,” is Ösung’s advice. “See what we share. No one seeks pain, sorrow, danger. Everyone seeks well-being, freedom, and happiness. If that is your basic outlook, then there is always a workable connection. And vice versa: If you don’t do that, you get stuck.”

“You always have influence on the chain of events.”

He also has advice for situations that people experience as hopeless. “Assuming that all living beings are connected to each other, all my thinking, speaking and physical actions matter. You always have influence on the chain of events. Directly in your environment and indirectly in the longer term. You are never separate from society, even if you don’t realize it. At the same time, this means that it is impossible not to take a social position because society is never separate from what you do.”

Realizing that your actions always have an impact means learning to see what is best to do at this moment. “When Russia invaded Ukraine, I wanted to sit in meditative silence in a square in Kiev.” He discussed the idea with his teacher and together they came to the conclusion that it probably wouldn’t be helpful at that moment in that situation. And that something else was needed to contribute to positive change in the long term. Many still remember the man who stood in front of a tank in Tiananmen Square in Beijing in 1989, when the Chinese authorities brutally suppressed student protests. “His action didn’t change anything in the short term. But everyone is familiar with this image through which his action continues to have an effect.”

Instead, Ösung joined the Chenrezig practice of Nalandabodhi, which consisted of chanting mantras aimed at ending all forms of conflict and aggression and bringing peace. “We quickly get caught up in a dynamic of thinking in terms of ‘friend and foe,’ ‘for and against,’ ‘good and bad,’ which is counterproductive. Retaliation, hatred and negative talk about others will not get us anywhere. We can also do something practical, such as supporting refugees.”

As a Catholic among Protestants

Karma Ösung grew up in Bakhuizen, a Catholic village in the otherwise predominantly Protestant-Christian Frisian countryside. “I learned a lot from that, such as weekly church attendance, the Eucharist celebration, and being an altar boy. But the ethical thinking in particular has stayed with me: making sure you do good.” After his parents divorced, the church disappeared from his life. In addition to secondary school in Sneek, life was filled with many sports, mountain climbing and rafting throughout Europe. So it was not surprising that he went to study sports marketing and management at the Rotterdam University of Applied Sciences as a seventeen-year-old.

But even though the church faded into the background, the questions of life remained. “My eldest brother gave me the book Sophie’s World and I became interested in philosophy.” That world-famous book by the Norwegian Jostein Gaarder tells the history of philosophy in novel form. “From the first page on, I couldn’t close the book and quickly decided that I wanted to teach philosophy and to make the world at least a little bit happier.” After completing his sports studies, he studied philosophy at Utrecht University and taught for seven years at a secondary school in Rotterdam. “A dream job that didn’t feel like work.”

Tibet

In addition to philosophy, he also became interested in the country of Tibet through which Buddhism also came into his life. “When I thought about Tibet and about the Chinese occupation and oppression, it felt like my own house was on fire.” After a Tibetan Buddhist retreat in 2011 in Dharamsala (India), Ösung started to focus on Buddhist meditation. He became a mindfulness trainer and student of Dzogchen Ponlop Rinpoche, the founder of Nalandabodhi.

“When I looked at photos of Tibetan Buddhist monks and nuns, it felt like I was looking at myself.”

With its western headquarters in Seattle, this sangha has centers and groups in North and South America, Asia and various European countries, including [the Dutch cities of] Rotterdam, Zutphen, Arnhem and Wageningen. A desire grew in him. Not only to go to Tibet, but also to become a monk. When I looked at photos of Tibetan Buddhist monks and nuns, it felt like I was looking at myself.

In 2017, he stopped teaching philosophy and went to Tibet: the journey he had wanted to make for years. There he visited, among other things, the Potala Palace in Lhasa: the winter palace of the Dalai Lamas, until the current one fled to India due to the Chinese occupation. “There, a sign states that Tibet has been part of China for centuries and that there is harmony with all ethnic minorities. This is not the reality. It is still an impressive palace but it also made me sad because of the life that has left this place.”

A Jewish Adventure

On his travels he met a new love: a female traveller from Israel “from a modern Jewish Orthodox background.” How would he reconcile this experience with his deep desire to become a monk which, in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition, requires celibacy? In turn, it was seen as defiant for an Israeli to pursue a love relationship with him, challenging the expectation to marry a Jewish man at a young age to start a family. At the same time, both realised: if we don’t try to see if this relationship works, we will regret it later.

Ösung – then ‘Fransiscus’ – settled in Jerusalem, where he studied Jewish Studies for a year and a half at the prestigious Hebrew University. “But I couldn’t ignore my inner voice, a desire for a monastic existence,” he says. After two years he ended the relationship. “That was the most difficult decision I had ever made in my life. But after the decision was made, I felt enormous peace without any doubts.”

During the two years that Ösung lived in Jerusalem, he obviously also experienced the tension between Jews and Palestinians, in Israel, Gaza and the West Bank. Ösung talks about the Disney film Raya and the Last Dragon, in which countries go to war because no one trusts each other and no one dares to take the first step to break through that mistrust. “That dynamic also plays out in Israel and all other conflicts. Who takes the first step to restore trust?”

Life as a Monk

He informed Dzogchen Ponlop Rinpoche, the spiritual leader of Nalandabodhi, by letter that he wanted to become a monk. A meeting with the teacher followed and the first steps were taken towards his initiation. When asked how he likes being a monk, he responds, “I feel at home like a fish in the water. It doesn’t feel like I’m doing anything that different as I had done before.”

The first time he visited the Netherlands as a monk and walked down the street with his mother in Friesland, she was a bit worried about the attention he attracted. “But now she thinks it’s okay. People who see me walking around in the Netherlands don’t see ‘Ösung’ or ‘Fransiscus’, they see a monk and a tradition that dates back to the time of the Buddha. I think it’s great to be part of a centuries-old tradition and I feel the responsibility that comes with it.”

Precepts

His daily life now consists of meditating, reciting, giving lessons, guiding meditations and organizational work. Life as a monk involves a large number of precepts that are written down in the Vinaya, texts from the time of the Buddha that serve as a guideline for daily life. Monks are subject to stricter precepts than lay people. Such as living a celibate life, in order to let go of attachment to worldly desires. And if he wants to travel, he must first ask his teacher for permission.

“A monk’s life means choosing simplicity.”

Why would you submit to rules that were drawn up thousands of years ago? “Every way of life has its advantages and disadvantages,” says Ösung. “That depends on your path. For some, that means a family life. For others, something completely different: some remain single and some become monks. The question is: what is my path? And what supports me at this moment?”

For him, the Vinaya helps to shape his life. “You let go of a lot of things, like possessions, being able to eat what and when you want, and wearing clothes based on your personal desire. That means choosing simplicity.” Ösung refers to the book Choosing Simplicity in which the Taiwanese Buddhist nun Bhikshuni Wu Yin explains that simplicity contributes to a harmonious life – as an individual but also in a community.

A Wandering Existence

As befits a Buddhist monk, he is ‘homeless’. That is, without a fixed place of residence or abode. “Just like the first monks, the followers of the Buddha, also wandered around. My abode is everywhere. I go somewhere because the sangha or my teacher asks me to.” says Ösung.

At the moment, he is in the Netherlands for a few months and he is sitting in his burgundy monk’s robe in Zutphen at the kitchen table of Sebo Ebbens, where he is staying for a few days. Ebbens, like Ösung, is affiliated with the Tibetan Buddhist sangha Nalandabodhi and the author of several books on Tibetan Buddhism and articles on Bodhi.

Ösung: “A sangha consists of monks, nuns and lay people, who are connected to each other. For example, we are invited to the meal, as I was invited here by Sebo and his wife. Then we talk about the dharma at the table.” And about how it can play a role in the world. There is currently a lot of pessimism and despair over violence, egoism, abuse of power and climate problems in the world. But Ösung points out that there are also people like Jane Goodall and Greta Thunberg, who show that you can keep hope alive through your actions.

In conclusion, he quotes the Seventeenth Karmapa, Ogyen Trinley Dorje from his book Interconnected:

“Our inner world is the pivotal domain for bringing about real change in the world that we all share. Neither social nor environmental justice is possible without significant changes in our attitude and the intentional behavior they give rise to. The transformation of our social and material world must begin within us.”

Leave a Reply